“Streaming Is Dead”: Hollywood's Profitability Problem in the Streaming Era

Streaming is convenient, but it’s destroying the old multi-revenue system that once made Hollywood much more profitable.

A Disney executive recently told Andor creator Tony Gilroy something shocking: “Streaming is dead.” That’s a bold statement coming from the same company that launched Disney+ with enormous fanfare just a few years ago. But when you look at the numbers, especially net income (profit) over the last 15 years, the statement actually starts to make a lot of sense.

I’ve been thinking a lot about this lately, and chatting with friends in the industry about the changes to the entertainment business. Now, don’t take this as some pity party for the loss in profits for massive corporations. This isn’t about that. The CEOs are still making their hundreds of millions of dollars each year (even if investors vote against them), but it is the working class people in Hollywood who are struggling as the studios battle a loss in profitability during the streaming era. This is why its so hard to make a profit as a filmmaker in the streaming era, and why so many productions are leaving Hollywood to try and cut costs and find any profit they can in this difficult new business model.

To me, it is really a simple math equation. The industry went from 3 month theatrical windows and selling DVDs at $20 a pop and to offering the entire Disney catalog for less than the price of a movie ticket. And its not just Disney. Warner Bros., Paramount, Universal - they all bought into this idea that streaming would be the future. And of course, it is the future in many ways. But that doesn’t mean it’s a good business.

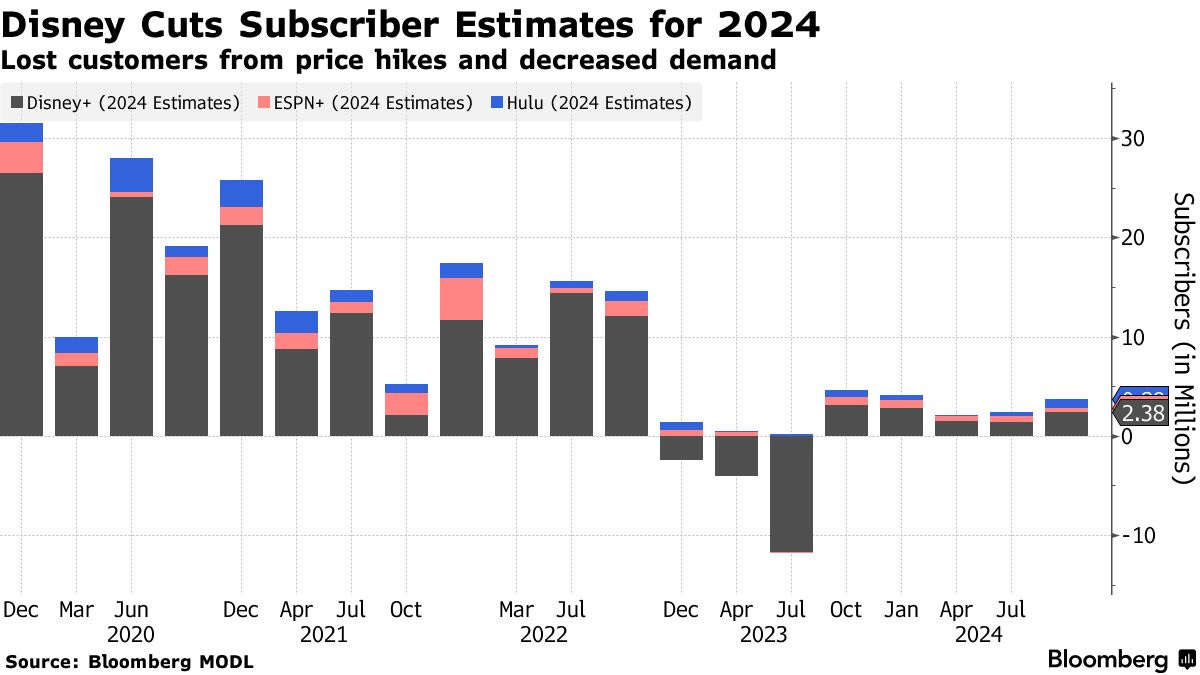

Let’s rewind for a second, using Disney as an example of how streaming shifted everything with real hard data to back this up.

Back in 2010, Disney was pulling in solid profits - about $3.96 billion in net income. Adjusted for inflation, that’s roughly $5.4 billion today. They were selling millions of DVDs and Blu-rays (Toy Story 3 sold 10 million units in 2010), cashing in on huge box office sales with long theatrical windows, and raking in advertising and licensing dollars from their cable channels. This was a not so distant time when people actually bought movies, not just access to a catalog. This was a time when the same piece of content could earn revenue in theaters, on disc, on cable, and again in syndication. Each step added to the profitability of a film and allowed for more creative risks.

By 2018, after Disney acquired 21st Century Fox, Lucasfilm, and Marvel Studios, they were flying even higher. Net income hit $12.6 billion, which is closer to $15 billion today after adjusting for inflation. And this was before Disney+ had even launched. It was all theatrical revenue, physical media, cable licensing, and merchandising. This was the peak of the traditional Hollywood model for profitability, and Disney was booming.

Now jump to 2024. Disney’s net income for the past year? $4.97 billion. Less than half of where they were in 2018, and even a drop in profit from 2010’s inflation-adjusted number. They are making less profit now than in 2010, even as they are pulling in more revenue than ever before. Why is that?

Well, here’s the thing: they’re spending way more to make content now than ever before. Streaming shows aren’t cheap. In many ways, they can cost just as much or more than the biggest blockbusters. A single season of a Marvel series can cost $200 million. The first two seasons of Andor cost a reported $650 million. And what did Disney get for returns? A single monthly subscription fee, often shared across households, generating low-margins and offering access to all of those expensive shows for a flat price. That’s not a great tradeoff.

The economics of streaming just don’t make sense when you stack them next to the old system. When a family used to buy a couple DVDs or Blu-rays per month, rent a movie or two, and maybe hit the theaters a few times a year, Disney could easily pull in hundreds of dollars per household each year. Now? They get $7 to $15 a month, all in. At best, with the highest $15.99 price tier, Disney is making $191 a year on streaming. If you share a subscription across households (I know I do, with several family members) the per capita revenue is even lower.

So what will they do? They will continue to increase the price. They will try to crack down on account sharing and make each subscription limited to a single household. But unless they hit ungodly fees like $50/month or more, the profits still won’t match what longer theatrical windows and a focus on individual movie sales and rentals via physical media and VOD (video on-demand) would offer.

A few years ago, Disney announced a Moana spinoff series for Disney+. It would have been another expensive project, all to get a few more subscriptions at $15/month. Disney realized this and changed course as well, and that series became Moana 2, reformatted as a movie and released exclusively to theaters. How did that go? They made over $1 billion at the box office, likely making hundreds of millions based on the film’s $150 million budget. Even if that budget was $250 million because of the last minute changes, the film would still be hugely profitable. There is just no way they would have made that much simply from new subscriptions to Disney+.

I know I picked on Disney, but this isn’t just a Disney problem. Even Warner Bros. seems to be walking this back. After trying the “everything goes to streaming” approach on HBO Max, they reversed course. Now they’re licensing movies to other services again, including ad-supported platforms. They even admitted it was a mistake to go all-in on streaming. And they’re not alone. Netflix is getting more selective with its output. Paramount is looking to sell. Disney is pivoting.

The statement from a Disney executive that “streaming is dead” is becoming an industry-wide realization that the promise of streaming, with endless growth, steady revenue, and more control, came with a catch. The money isn’t as good. They tried to become software subscription companies instead of entertainment companies, and that shift is biting them all in the ass.

Streaming is not going away. But the dream of having it replace every other revenue stream is fading fast. I can see that the pendulum is quickly swinging back. Theaters are starting to thrive again after a very difficult start to the 2020s. Physical media is seeing a boutique revival, and VOD sales are stronger than ever. People are starting to buy movies again, instead of endless subscription costs and rising prices. The system has become so fragmented and expensive, that consumers are stepping back.

2025 might be the beginning of the end for the “streaming bubble”, and I would love to see that bubble pop to go back to a more balanced world of entertainment with intentional viewing. I still see Netflix as the dominant force in this world, but they have become the new Cable TV. They have the sitcoms, the reality shows, the documentaries and true crime programming, live sports, and the “made for TV” style movies that we all grew up on. They will thrive as a replacement for that older technology. But the Hollywood studios need to get back to being studios - producing quality entertainment, utilizing existing distribution methods and licensing, and focusing on telling great stories instead of selling more subscriptions. The entire industry will be better off if they do.

Great write up! I thought about Disney's “vault” and about Mubi.

I wonder if Mubi's system of only keeping a film around for a month could coincide with disc releases or even theatrical releases. “See it remastered on the big screen,” or “buy it on blu-ray and keep it forever” or “catch it on streaming this summer” is a form of artificial scarcity, which I don't like, but it helps to empower consumers to make a choice (or several) based on their taste and spending power.

For those titans like Disney with a huge archive of properties, this seems like an avenue, not to mention their established pipelines already in place to produce theater and physical media content.

Nice post this lays it out clearly and succinctly